At its core, a sandwich attack is a form of front-running that primarily targets decentralized finance protocols and services.

In a sandwich attack, a nefarious trader looks for a pending transaction on the network of their choice, e.g., Ethereum.

As the name suggests, sandwiching occurs by placing one order right before the trade and one right after it. In essence, the attacker will front-run and back-run simultaneously, with the original pending transaction sandwiched in between.

These attacks often appear in the wild due to the public nature of blockchains since all transactions can be observed by anyone in the mempool.

Alternatively, smart contracts may contain functions without access restrictions performing such a trade. These functions often exist for claiming LP reward tokens and immediately swapping them for some other token using a DEX.

Practical Implementation

Table of Contents

A victim transaction trades a crypto-currency asset X (ex: ETH, DAI, SAI, VERI) to another crypto-asset Y and makes a large purchase. A bot sniffs out the transaction and Front-Runs the victim by purchasing asset Y before the large trade is approved.

This purchase raises the price of asset-Y for the victim trader and increases the slippage. Because of this high purchase of asset Y, its price goes up, and the Victim is forced to make the buy at a higher price of asset Y. Finally, the attacker sells this asset Y at a higher price once the victim’s transaction has completed.

Two Possible Scenarios:

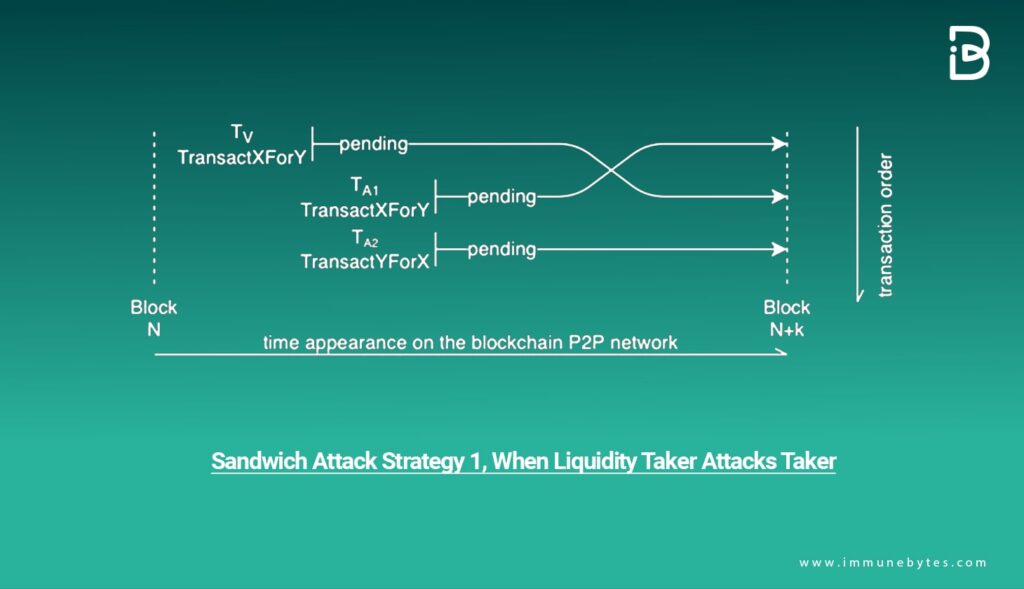

Liquidity Taker vs. Taker

For example, if a regular market taker has a pending AMM transaction on the blockchain, the culprit can emit subsequent transactions — front-running and back-running — for financial gain. As the liquidity pool and asset pair have three pending transactions, miners will decide which is approved first.

If the culprit pays a higher transaction cost, that is, the gas price, than the other individual, there is a higher chance for the malicious transaction to be picked up first. It is not a guaranteed outcome but merely an illustration of how easy it can be to attempt a sandwich attack.

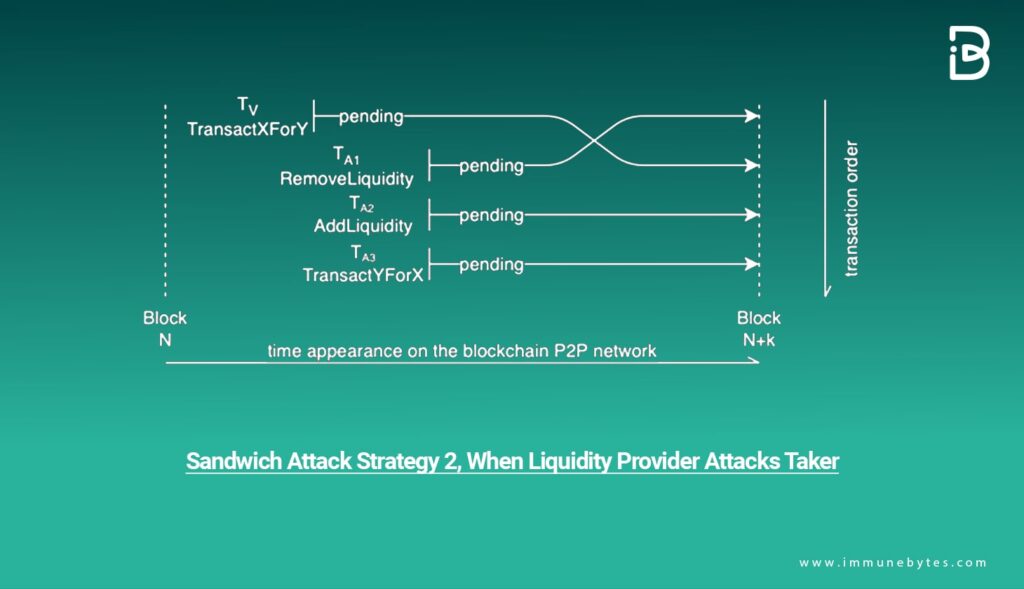

Liquidity Provider vs. Taker

A liquidity provider can attack a liquidity taker in a very similar manner. The initial setup remains identical, although the bad actor will need to perform three actions this time.

First, they remove liquidity — as a front-running method — to increase the victim’s slippage. Second, they re-add liquidity — back-running to restore the initial pool balance. Third, they swap asset Y for X to restore the asset balance of X to how it was before the attack.

Key Vulnerabilities

Let’s have a closer look and analyze what makes a sandwich attack.

Automated Market Maker (AMM)

This is a predefined pricing algorithm that automatically performs price discovery and market-making based on the assets in the liquidity pools. The AMM allows liquidity providers to watch and follow the market, then set the bid and ask prices. Liquidity takers, in their turn, trade against the AMM.

Price Slippage

Price slippage is the change in the price of an asset during a trade. Expected price slippage is the expected increase or decrease in price based on the volume to be traded and the available liquidity where the expectation is formed at the beginning of the trade.

Expected Execution Price

When a liquidity taker issues trade on X/Y, the taker wishes to execute the trade with the expected execution price (based on the AMM algorithm and X/Y state), given the expected slippage.

Unexpected Price Slippage

The difference between the execution price and the expected execution price.

Unexpected Slippage Rate

The unexpected slippage over the expected price.

Remediation

Here are some pointers and insights to help you steer clear of sandwich attacks:

- As a trader, you should avoid executing high-value transactions during peak hours, especially when the market volatility is high.

- Traders should use slippage detection and protection tools at all times. Note that even if the transactions do not go through due to slippage protection — keeping traders safe — the gas fees or transaction costs must still be paid.

- Traders must double-check every aspect of the transaction, including the gas fees, exchange rates, and the amount before trade execution.

- Traders must never use insecure networks or channels while interacting with a liquidity pool.

- DeFi platforms are actively integrating anti-front running strategies like flash bot transactions to connect traders directly to trusted validators to get the transactions through.

- Liquidity pools are exploring new MEV blocking solutions, thwarting the concept of sending and validating a transaction with higher gas fees.

Case Study: The Uniswap Attack

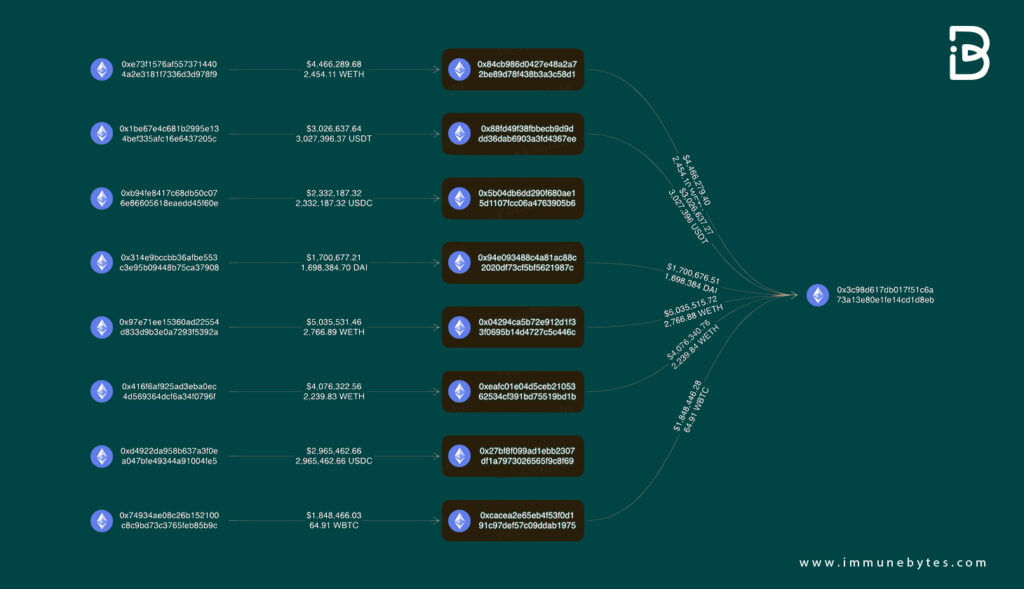

Rogue Ethereum validator stole over $25 million worth of cryptocurrencies from an Ethereum MEV bot conducting sandwich trades. The hacker stole over $25 million from the Ethereum Maximal Extractable Value (MEV) bots and stored the amount in mainly three different addresses.

They kept a significant amount in 0x3c98, worth over $20 million. A relatively small chunk worth roughly $2.3 million and $3 million is located in 0x5b04 and 0x27bf, respectively.

The Fund Movement

The MEV bots use various strategies, one being the sandwich attack. An MEV bot spots someone else’s intent to buy a coin and sets itself up to profit from the small price appreciation that the other person’s bid will likely cause.

The bot jumps the line to purchase the coin at a fraction less of the value under trade, essentially front-running the trade.

Then, after the purchase by the mark in the middle goes through, the bot tops off the sandwich by automatically selling the token at a profit, and as the bots executed the sandwich trade, the rogue Ethereum validator replaced the reverse transaction when they tried to close the trade.