What is Front-Running?

Table of Contents

In traditional stock markets, front-running is a term that refers to the unethical or illegal practice of a financial market participant (such as a broker, trader, or firm) executing trades based on advance knowledge of pending orders from other clients. It involves taking advantage of privileged information to gain a financial advantage at the expense of other market participants.

In the context of a blockchain-based system, front-running refers to a malicious practice where a user or a group of users exploit advanced knowledge of pending transactions to gain an unfair advantage over other participants in the network. This type of attack is prevalent in decentralized blockchain systems, such as Ethereum, where transactions are executed in a specific order based on their arrival time in the mempool.

How Front-Running Occurs?

Pending Transactions

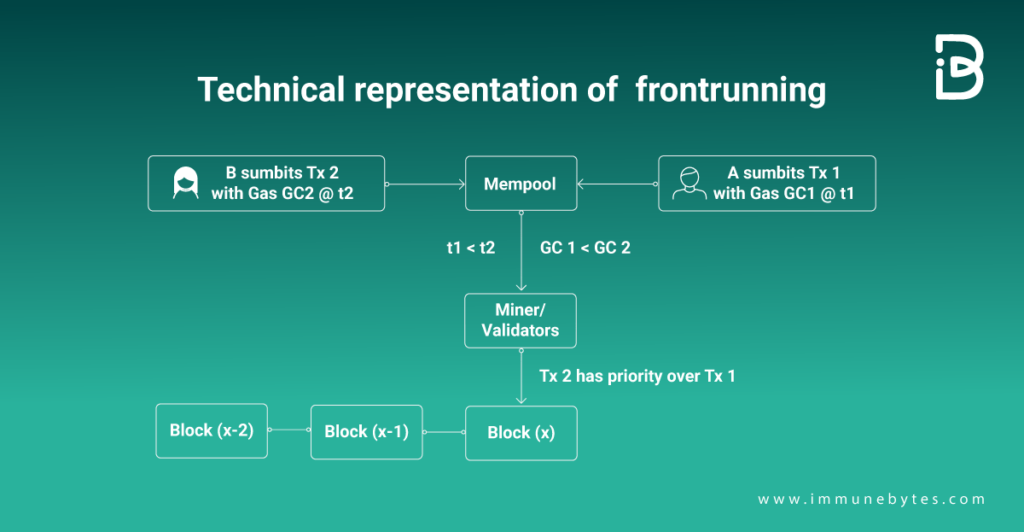

When a user initiates a transaction on the blockchain, it is broadcasted to the network and added to the mempool. The mempool is a temporary storage area where pending transactions wait to be included in a block by miners (or validators).

Observing the Mempool

In a front-running attack, an attacker closely monitors the mempool, looking for specific transactions that indicate a particular action about to take place. For example, they might look for transactions that trigger smart contracts or interact with decentralized applications (DApps).

Following are the factors which identify a transaction attracting adversaries to extract any and all benefit they can, provided some minor changes in the flow of a transaction.

- Public Information: The mempool is public, meaning that anyone can inspect its content. This transparency is a fundamental feature of blockchain technology, ensuring that everyone can verify transactions independently. However, it also provides an opportunity for potential front-runners to monitor pending transactions.

- Identifying Profitable Transactions: By monitoring the mempool, an attacker can identify transactions that could be profitable if front-run. For example, in a decentralized exchange, a large buy order for a particular token will likely increase its price. If an attacker sees such a transaction in the mempool, they can place their own buy order for the same token, hoping to sell it later at a higher price.

- Extracting Transaction Details: When a transaction is in the mempool, its details are visible to all. This includes the sender’s address, the receiver’s address, the amount of cryptocurrency being sent, and the gas price. In the case of a smart contract interaction, the method being called and its parameters are also visible. This information can be crucial for an attacker. For example, if the transaction is a call to a specific function in a decentralized exchange’s smart contract, the attacker can see the exact details of the trade.

- Identifying the Beneficiary: The attacker’s goal is to execute a similar transaction but change the beneficiary to their own address. By inspecting the transaction details, they can identify the original beneficiary and replace it with their own address in the front-running transaction. This could be done in various ways depending on the specific blockchain and the nature of the transaction. For example, in a trade on a decentralized exchange, the attacker could replace the recipient address of the trade output with their own.

- Timing: Timing is crucial in a front-running attack. Once the attacker identifies a profitable transaction, they need to act fast. They need to create and broadcast their own transaction before the original transaction gets included in a block. This is why front-runners often use bots to monitor the mempool and automatically create and send transactions when they identify a front-running opportunity.

Placing a Front-Running Transaction

Once the attacker identifies a target transaction, they quickly submit their own transaction with a higher gas price (transaction fee) to the network. The higher gas price incentivizes miners to prioritize their transaction over others, including the target transaction.

Miner’s Incentive

Miners, who have the power to select which transactions to include in the next block, are economically motivated to prioritize transactions with higher gas prices because they earn more in transaction fees by doing so.

Higher Gas Prices

In most blockchain networks, including Ethereum, transaction order is influenced by gas prices. When multiple transactions are waiting in the mempool, miners typically prioritize transactions that offer higher gas prices. This is because the gas price is the miner’s reward for including the transaction in a block. In a front-running attack, the attacker deliberately sets a higher gas price for their transaction. By doing so, they essentially “bribe” the miners to include their transaction in a block before the original transaction. This is a key part of the front-running strategy: even though paying a higher gas price reduces the attacker’s profit margin, it increases the chances that their transaction will be executed before the original transaction, thus ensuring the success of the front-running attack.

Transaction Ordering

The miner, when building the next block, selects the attacker’s front-running transaction and includes it before the target transaction. As a result, the attacker’s transaction gets executed before the target transaction, giving them the advantage they sought.

Impact

Depending on the context, the front-running attack can be used for various purposes, such as frontrunning trades on decentralized exchanges (DEXs), getting ahead of other participants in token sales, or gaining unfair advantages in other blockchain-based applications.

A Practical Implementation

Let us assume that Bob is swapping ETH for MATIC from a Uniswap pool. Now, an attacker monitors his transaction by scanning the mempool, and when he finds his transaction and he immediately places two orders.

Attacker’s 1st Txn: Swapping ETH for MATIC paying higher gas fees

Attacker’s 2nd Txn: Swapping back MATIC for ETH paying lower gas fees

- First, the attacker will front-run Alice’s transaction with the same swap (swapping ETH for MATIC) and thus increasing the price of MATIC.

- Now, after the price is increased Alice’s transaction is executed and she ends up paying more ETH for MATIC with higher price slippage.

- Once the victim’s transaction is executed, the attacker will swap his MATIC back to ETH and make a profit.

Remediation

To minimize the chances of front-running, one can follow the below measures:

- Encrypt and Commit Scheme: This method involves encrypting sensitive transaction details and revealing the decryption key only after the transaction is confirmed in a block. This prevents front-runners from observing the content of the transaction and gaining an advantage.

- Zero-Knowledge Proofs: Zero-knowledge proofs allow one party (the prover) to prove to another party (the verifier) that a particular statement is true without revealing any additional information. By using zero-knowledge proofs, a user can demonstrate that they have a valid transaction without revealing the transaction details, reducing the possibility of front-running.

- Order Matching Mechanisms: Implementing order matching mechanisms in decentralized exchanges (DEXs) can help reduce the impact of front-running. By executing trades based on the order in which they were received rather than prioritizing higher transaction fees, the advantage gained by front-runners is diminished.

- Delay Mechanisms: Introducing a small delay between the broadcasting of a transaction to the network and its execution can help mitigate front-running. This delay gives all transactions a fair chance to be included in a block without being preempted by front-runners.

- Private Transactions: Solutions like Flashbots emerge as a necessary counter measure for the adversarial nature of blockchain’s MEV generalized front-runners which allow users with enough incentive in executing a transaction that they are willing to share with a closed circle of block producers.

- Layer 2 Solutions: Utilizing layer 2 scaling solutions, such as payment channels or sidechains, can help reduce the impact of front-running by enabling faster and more private transactions off the main blockchain.

- Anti-Front-Running Smart Contracts: Developers can design smart contracts with anti-front-running mechanisms explicitly built into their logic. These mechanisms can impose penalties or fees on front-runners or include verifiable delay functions (VDFs) to make front-running more difficult.

- Regulatory Measures: In some cases, regulators may intervene to enforce rules and regulations against front-running activities, especially if they involve malicious intentions or manipulative behaviors.

It’s worth noting that while these remediations can help reduce the impact of front-running, no solution is entirely foolproof.